The solo exhibition Analogy was presented at Berg contemporary in 2022. The exhibition consisted of a photographs, text work and installaition. Photo credit Vigfús Birgisson.

It serves existence, itself, and nothing

A dialogue with the artist

Jóna Hlíf creates gaps: she spots gaps that exist and are familiar in cultures; she discovers previously-unknown ones, like an explorer; she makes new and unexpected connections. She plays around with generalised views of the world and historical time, breaking up history, thawing out the past from the freezer, freezers. Meaning is a phenomenon that changes, spreads and mutates. Jóna Hlíf gives warning – she retrieves valuables from the ashes: don’t forget where you came from, I seem to hear reverberating. She juxtaposes similar and dissimilar times, similar and dissimilar places, similar and dissimilar words – thus illuminating the gigantic gaps that live and pulsate between sensation and thought.

Sometimes she bridges the gap – for instance with colour – and by the colour she intensifies and soothes the gap that arises in the observer’s mind – in this final act of a trilogy: The Colour Purple. At the same time the observer perceives a mirage with a mirage within a mirage. And the mirage trembles beauty. That is called magic.

Note on the word magic:

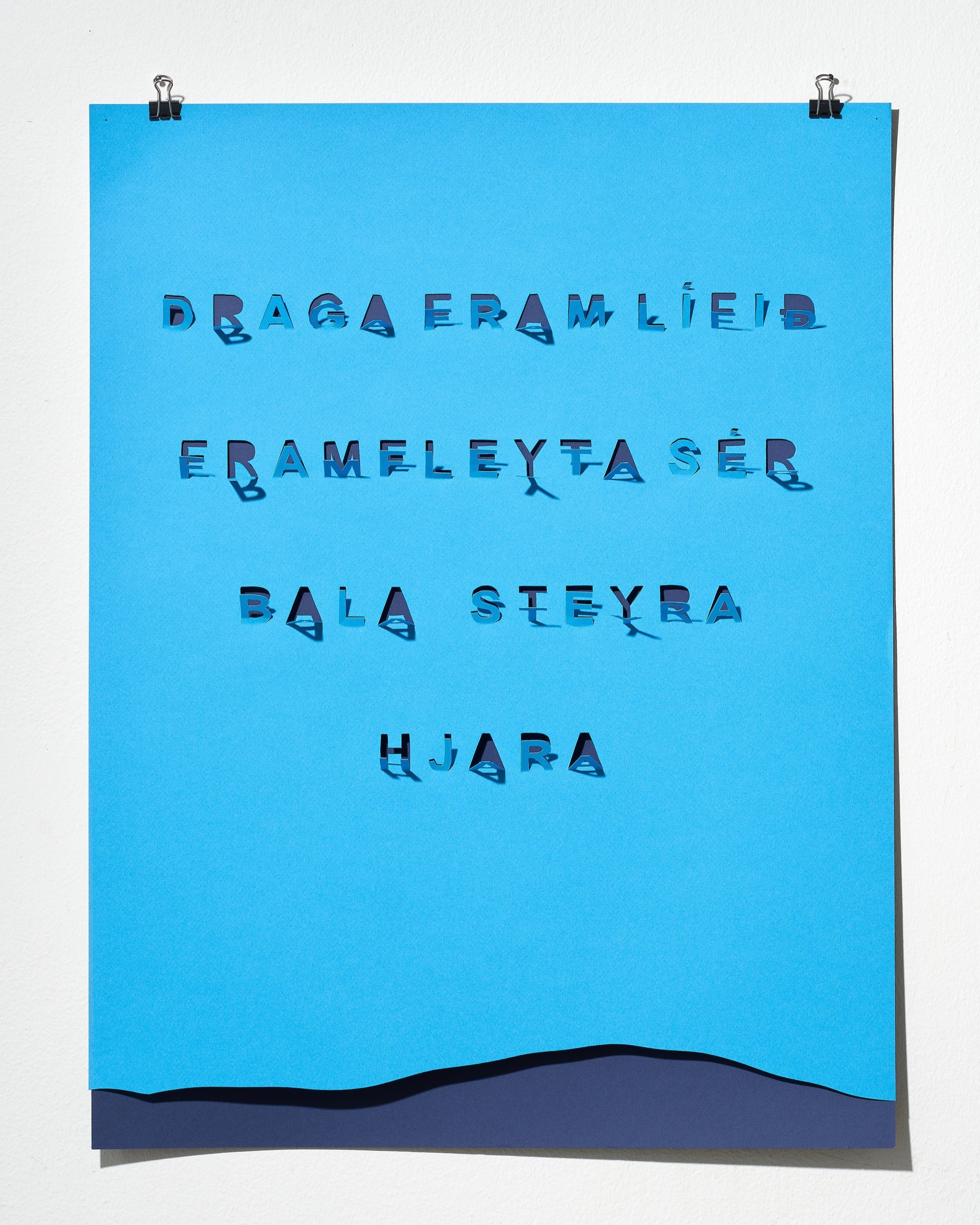

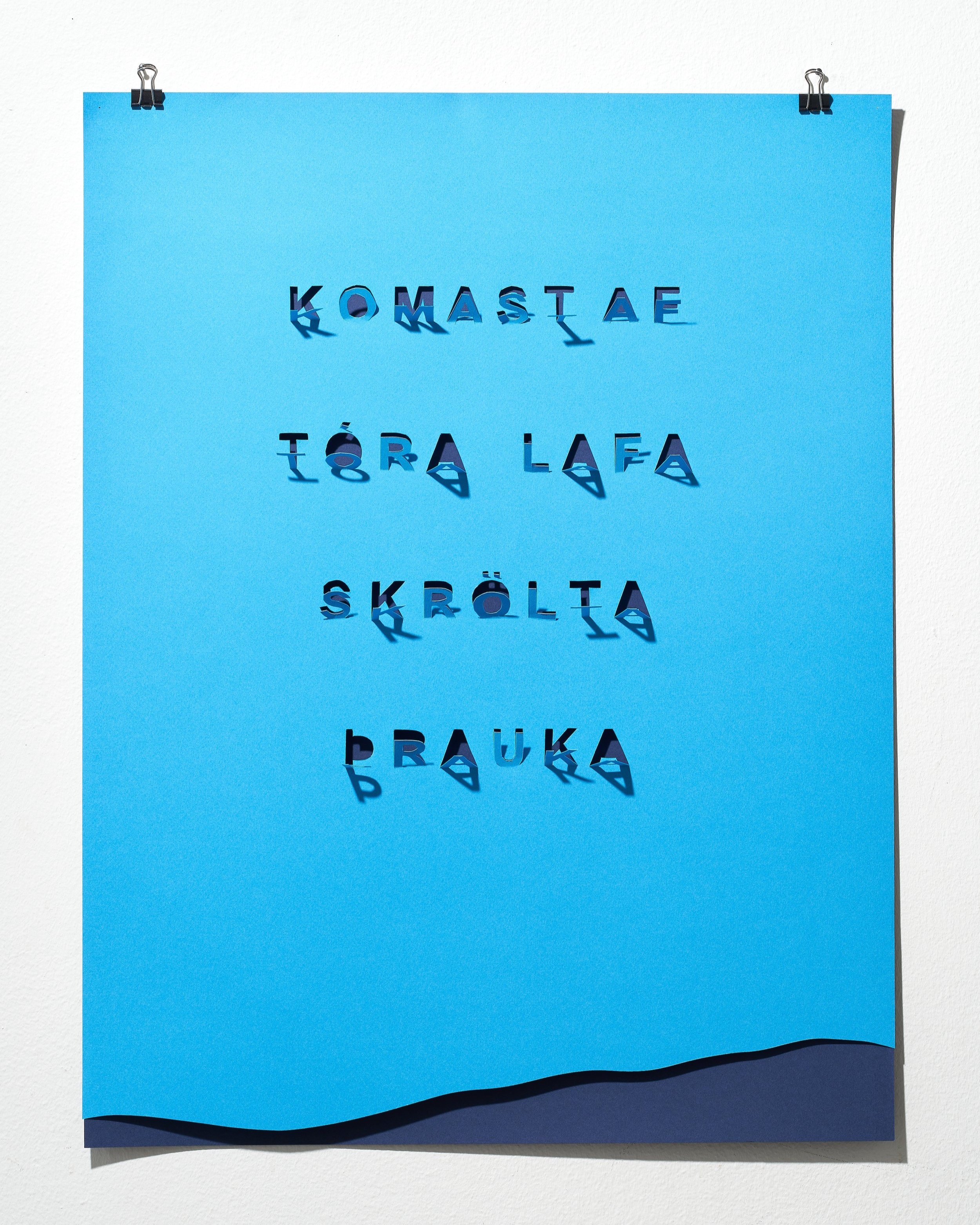

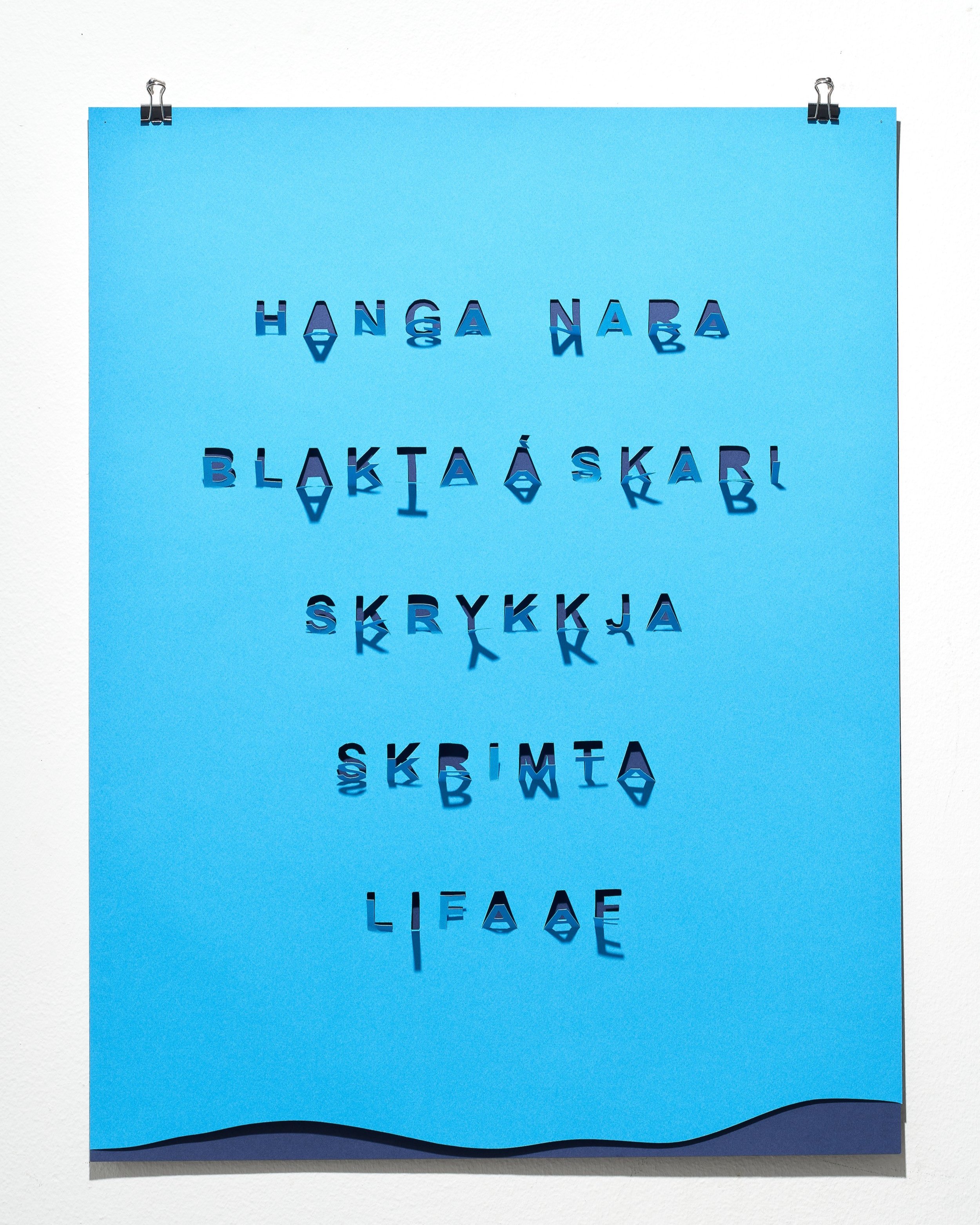

The allure/enticement/attraction of art is different in nature from the allure/enticement/attraction of the Lorelei dream-factory. Art does not trick me into buying a ticket to a desert island. Art removes me from the subject and it propels me outside the subject. The subject is its substance: the medium. In her third show, under the title Líking / Analogy (the first show in the series was More Than a Thousand Words, whose colour was blue, and the second, Cottongrass Flames, yellow), Jóna Hlíf uses in this instance photographs, words, rainbow paper, straws, wood, lines and, of course, the colour purple – and [in addition to the gaps] material otherwise unnoticed by the eye; the exhibition itself explains this best: what I never saw. The impact on me of seeing Jóna Hlíf’s works: It is as if my mind ripples, trembling between the thought systems of the brain. I put some questions to Jóna Hlíf. In general I understand her answers better than my questions.

My dear Jóna Hlíf, “Everything has significance, nothing has meaning” appears prominently in your exhibition. To approach what I see as a cognitive viewpoint, may I ask you: what is untranslatable?

What is unsayable is untranslatable. Images are untranslatable – they simply signify what they are, yet they signify so much. Often, in fact, images, and especially works, don’t want to signify anything – they simply want to be sensed, to entail an experience of aesthetic perception. (Some) words are untranslatable, or at least they have no equivalent, no direct parallel, no sister or brother on the other side of the line laid down by understanding. Languages are some of the most remarkable human inventions – the only ones which create an absolutely new dimension within existence.

And what is translatable?

What is sayable. But it is so beautiful that in Icelandic the two words þýðing and merking can both be conveyed by one word in English: meaning. Þýðing (= meaning, translation) is an ambiguous word, i.e. it signifies purpose, but what is translatable can be translated on the premise that we have agreed that a similarity exists between two words in different systems, in separate languages. People have reached agreement, conferred in dissimilar systems, created books and put into them images of the same things, and assigned different words to the same thing in the different systems.

Wow! Thanks. And loanwords move onto new evolutionary paths – the original meaning is distanced from its origin, leaving the root with traits of its great-grandmother.

Yes, and problems sometimes arise – hesitation, gaps, momentary uncertainty, awkwardness – and it is just those problems that are so fascinating. What is the precise equivalent of the Japanese word ikigai? Is it simply purpose? What about komorebi? Can we convey it as sunlight through trees? Or does each word have a deeper content behind the meaning – a root or historical connection that cannot be made translatable? Like all the Icelandic words for living, for getting by, such as skrimta – and the words for dying, like farast. And that synonym for hard labour, brauðstrit, literally toiling for bread. There is no lack of diverse vocabulary in Icelandic.

Yes, the inhabitants of a rocky island long devoid of trees knew nothing of the komorebi sometimes captured by artists, whose achievements hang on the walls of international art museums. Icelandic has been shaped by the rigors of a harsh existence, as revealed in your works.

Yes, but not only in my works. It’s a root that is still only half-forgotten by many, as I see it. Some of those words – lafa, nara, skrykkja [dangle, linger, scrape by] – have no significance for me, while I still use others, such as hjara, skrimta, tóra [expressions for eking out a living, hanging on, getting by]. The same applies to all the Icelandic words for snow – they all bear witness to that changeless, bleak battle of existence. But that which is translatable is in some cases remade, or half- mediated. And maybe the translatable is a lie, too. Or deception. Self-deception?

Can we maintain that when a person learns Icelandic as a third language, learns to translate “their” words into Icelandic, to think in Icelandic, they will be offered a full share of what it means to live in Iceland? Or is there always a fine or visible line between Icelandic and learned Icelandic? Is translation or equivalence between languages or social groups a lie, or a deception?

Good question. And I tend to believe that everything ultimately flows together on course towards eternity, but the most unjust of all injustices is how horribly long injustice takes, at such great cost in sacrifices and lives, which ought to be banned.

I agree with you. The worst thing about injustice is its relentlessness.

Oh, yes, absolutely. But what purpose does art serve – it’s not Netflix or design or a propaganda machine – if indeed it serves anything?

I want to say existence. It serves that. But mainly itself, and nothing.

I think that make good sense: it serves existence, itself, and nothing. Does art have meaning/significance in the present day? During the fourth industrial revolution? Art is sold on Instagram, and that is where new artists attract attention, so I am told.

Yes, in the sense that it has a purpose (while being purposeless in its own way). Works of art are still shaking up and stirring, sparking debate, creating ideas, offending and mesmerising. The fourth industrial revolution is transforming how it is mediated; but as art takes place mostly in the real world, between four walls, the fourth revolution is not having a big impact on it (I think).

Is life in art lonely in the western world, where all sort of possibilities of “time rush” are available?

I think that life in art is and will remain lonely in its own way – all creation is lonely in its way – not just because of the time rush. It can be good to have a time rush, but then there is a flow of information and more information and even “new” information, and that flood becomes dominant, even overwhelming. In that flow, and in face of the oceans, or mountains, of new material being produced – music, literature, film, visual art – it is easy to become lonely, if one is not already inundated.

I feel that everyone around me – composers, authors, artists and filmmakers – is saying the same: there is so much new art, so much is being produced. But I have decided not to let that burden me or fuel fears. One cannot experience all of it or gain an overview of it – it will be a bit chaotic, a chaotic world where each person does their own thing. But then we should simply follow the

example of farmers: keep on ploughing. There will always be another summer – the rest sinks into the ground, whether we call it soil, or history.

Mmm, yes, quite. And where better to aim than there: into the earth? But what is the significance and meaning of being an artist?

For myself: Lively Mondays. For society: the click of smartphones (pessimistic answer) or attitudes (optimistic answer). For life: Copies of ideas from my head.

What is the position of a woman artist in a patriarchy?

She will always stand outside the patriarchy, as it is defined. But a woman artist creates, and she can take part in creating a healthier framework for communities

than the patriarchy has done. As a woman artist she has a duty to have an influence and take part in creating a society that entails a healthier framework than the patriarchy. She either does that alone, herself, through her work or, I think more probably, she does it in community with others. As a mother, the woman artist may give birth to future fathers within the patriarchy. As daughter she may have a father in the patriarchy. As a sister she may have a brother in the patriarchy. As a girlfriend or spouse, she may have a life-partner in the patriarchy. These are all excellent opportunities to have an impact on the patriarchy and the position of women (artists) within it.

Exactly. And you both show and tell – and not only that. Something beyond that. Are you conscious of your purpose, if there is one?

Yes. Everyone want to understand, and I do so by telling as well as showing. But it is too limiting to tell everything.

Yes, it’s too limiting, absolutely ��. Do you want to tease me? Touch my brain activity? Guide me? Change the world? Then comes a question which

is silly, because it is obvious from your art shows, but I’ll ask it, so it is on the record: Is your art political?

Yes. I like to tease. Teasing is a form of control, but also a stimulus to alter self-control. And one teases in the same way as one makes a person laugh: with

words, with pictures, or with something physical (intimacy). I like to tease, or rather perhaps make a game. There are certain games in

progress in all my exhibitions, and in this one the underlying themes are: Lines and boundaries.

There’s the phenomenon of line, and how lines – both sentences (words) and outlines – establish boundaries, lay down rules or other divisions, distinguish between one thing and another. I want in a sense to make the perfect line, and to understand what can make a line perfect. Then, when I’ve got it, I’m seized with the desire to scribble over it – as one did with pictures as a child: Making

something, then destroying it, due to some compulsion that came from exactly the same place as the desire to create it.

In three recent shows I have been playing, teasing others, on the basis of the classic themes of art: the unique and the unusual. Iceland is in a sense both unique and unusual, and neither unique nor unusual. And I’ve been working with words, phrases and context in a certain light between words, taking account of visual images which are ultimately concerned with what is Icelandic or seems “Icelandic.” You see. Iceland is a word, and words make Iceland. When one starts to play around with these phenomena, it becomes clear that the phenomena of lines determine our thinking. We are always drawing lines. A line between ourselves and the world. A line between words. Establishing a boundary or placing an equals sign between languages. We find a line in nature to establish a boundary: There is a mountain, and here no mountain. Call it mountain. Say the glacier begins here and ends there, call it Jökulsárlón (= Glacial River Lagoon). Draw lines in the sand, determine what is one thing, and what is another. Use lines to control the world. And it can be fun to play with the lines, and even to try to obliterate them. Even to make new lines that need not be anything unusual, but may be, for instance, outlines of an imaginary mountain or glacial lagoon (seen from above).

This entails a certain policy, a certain critique: What is, in the end, “Icelandic”? How do we draw a line between ourselves and others, and why?

Some of my art is pure politics. I think, for instance, that this show is highly political, although it may not appear so at first glance. And I sometimes find politics tedious, and I don’t want art to be only that, i.e. political. So some works are more political than others. But other works may be read or interpreted politically. Many of the works in this show have sprung from the books Surfaces and Essences by Hofstadter and Sander and Að hugsa á íslensku (Thinking in Icelandic) by philosopher Þorsteinn Gylfason.

My art is always made in connection with, and in proximity with, words – even languages as phenomena. I feel that both are somehow so human that theybelong to all branches of the arts – not only literature, authors, poets. Maybe that’s wrong. Or maybe right? Perhaps there is no difference between a lyrical work in textual form and a visual poem, other than context? Perhaps literary forms belong to literary art, while words may belong to all art forms? Sometimes it seems to me that all art, all creation, regardless of the art form, entails play with light/sound, idea(s), forms, words and deception. Words may be covert or overt, but they are always close to ideas.

Words are subjects, and lyrical and political art are sisters, perhaps twin sisters. Is your art feminist?

I have certainly made feminist pieces, but I don’t consciously direct my art only in that direction. I am guided by ideas and the subjects I want to address. Some of

the works I have made are very clearly feminist, while others can be read or interpreted as feminist, just as in the case of political elements of my art. Works are, really, gender-neutral, because material is generally gender-neutral, as I see it. But the choice of material, what is done with it and how it is presented in my shows is, in its own way, feminist, and always will be. I am a woman, after all.

Yes. And one final question: What do you do to escape the irritations of our time: do you have a magic cloak of invisibility?

My answer is very Icelandic, very Reykjavík: I get out of town. I feel that phrase is so strongly bound up with what it is to be a person living in Iceland, in Reykjavík, today. I regularly resolve to get away from my computer. I switch off my phone for as long as possible, and go in search of sea, sand, trees, vegetation and the outdoors.

Thank you so much, Jóna Hlíf, this is the ideal place to end. And congratulations on your exhibition!

Thanks 🙂

Text by: Kristín Ómarsdóttir, in conversation with the artist.

Translation: Anna Yates.